About Winslow Loves You! '25

Winslow Loves You! '25 is a community-based printmaker approaching print as a physically hands-on endeavor through emotional investigating done by learning from their own and others’ Queer experiences. Practicing out of Portland, ME while pursuing a BFA in printmaking at Maine College of Art & Design with an expected graduation date of May 2025. Winslow was born and raised in Charlottesville, VA in a disrupted household as a disjointed body in a traumatized city. Winslow works through printmaking to provoke community resistance and harm reduction in order to heal our inhabited bodies and spaces.

Interview

What year will you graduate from the College, and what do you study?

I am studying in the Printmaking department and will graduate in 2025.

What artistic media do you primarily work with, and what drew you to them? Do you feel they lend themselves to exploring queer narratives?

I first started printmaking when I was a teenager, and what attracted me to it immediately was its hands-on nature and the physicality of the art. I find it useful to touch what I'm making and understand what I'm doing by having it physically in front of me. I also love that the print lends itself to the intimacy of working with that art form.

And I think that that works well with queer narratives that I usually have in my artwork. There's a relationship there with the intimacy of queer relationships and queer art and then the intimacy of getting to work with a craft.

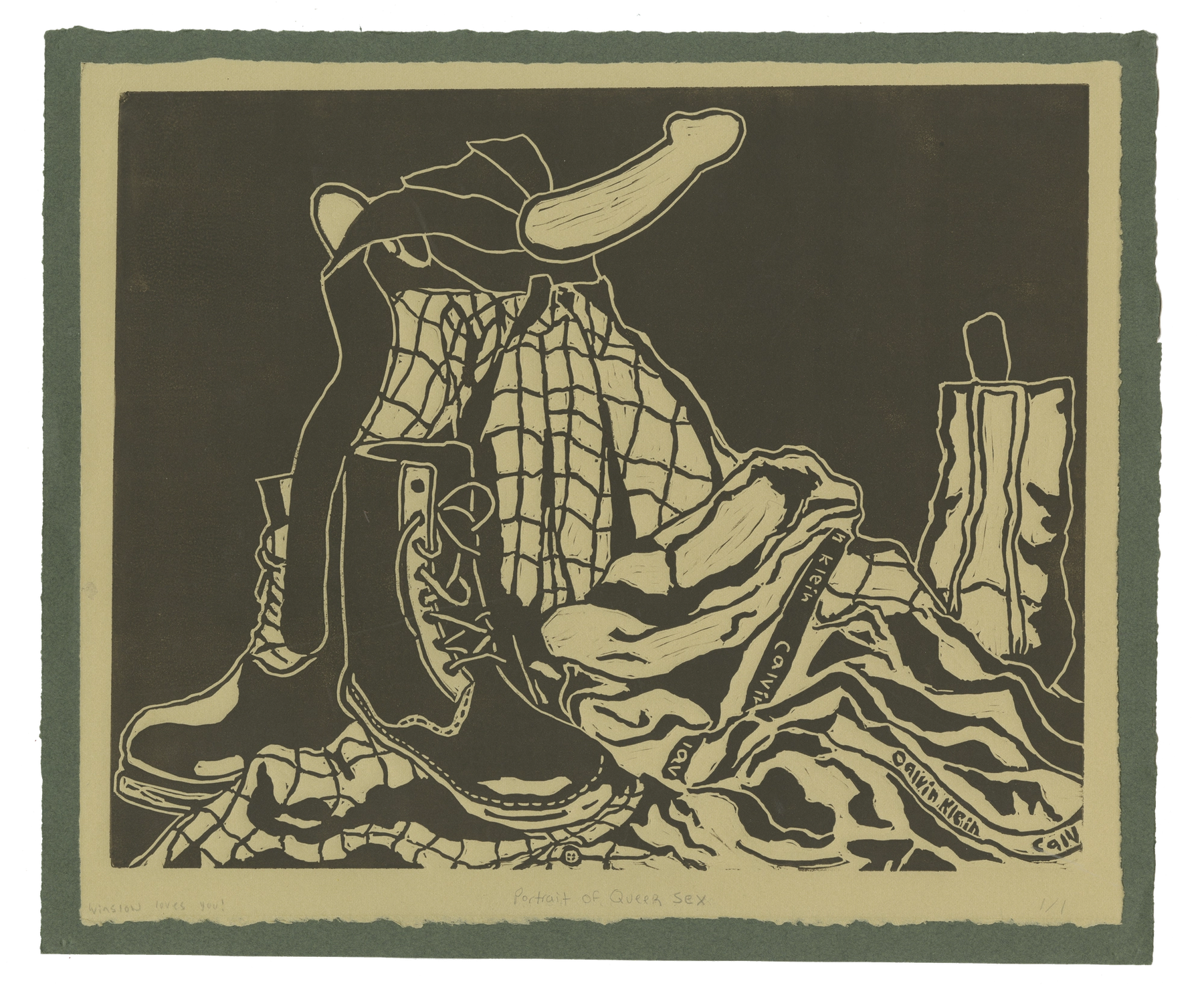

Winslow Loves You!

Portrait of Queer Sex

Linocut, 15x12.5 in, 2022

How does your lived experience influence or shape your artistic practice and the themes you explore in your work?

A lot of my art is a baseline expression of what I'm going through, and getting into more serious art-making practice happened because of traumatic events I have gone through. I needed an outlet to express those things and get them out of my brain and subconscious. Through that and making artwork, I have become more of myself.

It's hard to put a label on my identity. I don't like to put labels on identities, so for me, solidifying my identity and becoming more accepting of that has meant accepting my fluidity and accepting gray areas, and accepting that I am queer. Our experiences, the things we practice daily, and the items we interact with daily are more telling of identity than a label could be.

What are some of the biggest influences on your work? How does your community impact your artistic voice and vision?

Well, I'm very much influenced by contemporary queer artists, of course. I'm very inspired by Tom of Finland and John Waters movies and all these very out-there, explicitly gay things. I like to think my work is in conversation with those artists, specifically, the queer scene in New York in the 60s and artists like Nan Golden and Nancy Grossman. My artwork definitely has a place within the context of contemporary art history.

It's interesting to me to be able to be in conversation with that history as a queer maker, and where printmaking is now is very community-based and very queer. I enjoy being able to work with commercial art and then put this queer spin on it and make it my own.

Winslow Loves You!

More Than Words Can Say

Materials, 10x10 in, 2023

How does your work fit in (or not fit in) to the narratives of art history?

In art history, one of my inspirations for getting into printmaking was attending an Edvard Munch exhibition. I love how he uses wood grain, grimy, disintegrated images, and imagery. He does not shy away from being gross and revealing and fully showing all of his emotions, all of the things that he's feeling, and all of these complicated mental battles that he had. That was very inspiring for me to see.

I read a lot of David Wojnarowicz. He was making all this artwork about being queer in the middle of the AIDS crisis and about dealing with his own identity and his AIDS diagnosis. And what was inspiring to me was how he was unapologetically himself. He published all these narratives of the private lives of queer individuals in New York City. There are some great essays about taking the private life into the public and what that does for queer people to be able to be seen and to be able to feel heard.

What do you see as the future of queer art and its role in broader cultural conversations around LGBTQIA+ issues?

I place importance on breaking down the barriers between heteronormative society and queer culture. I want to highlight the private realm of queerness and normalize the things that a lot of people in this world aren't aware of. I've made these transsexual education prints, which were prints of vaginas after receiving testosterone and noticing the changes that we see in genitalia through hormone replacement therapy. It's so important to make people aware of what queer people look like, what we're going through, and what's happening to us.

What are some of the recurring motifs, symbols, narratives, or themes that appear in your work, and what significance do they hold — particularly in relation to queer themes and experiences? How do they counter narratives of heteronormativity?

My artwork uses a lot of very explicit motifs, including sex toys, naked bodies, body hair, and drug paraphernalia. Other queer people can relate to and understand these motifs that some audiences could see as gross, but I want to show that they are part of everyday life for others.

Winslow Loves You!

Transsexual Education 2

Linocut, 2022

Do you see your work as a method of resistance? If so, how does that resistance manifest itself in your work?

Explicit imagery is my resistance. I'm thankful for this very supportive art school scene that we're in, where it doesn't feel out of place to put a painting or a print of a dildo on the wall. I think about resistance in the context of a larger art audience, and I think about a straight, suburban atmosphere and how works like mine can interact with that. What's interesting to me is that sex happens in those households—it's just hidden. Bringing the private into public feels like resistance to me.

What are the most fulfilling or gratifying aspects of the creative process for you?

The physicality of printmaking is so satisfying, and getting to work with the craft means realizing these ideas that rattle around in my brain that feel like they need to be outside of me—they need to get out of my body and out of my brain. It is such a relief to get those ideas out and have them in physical print that somebody can hold and touch.